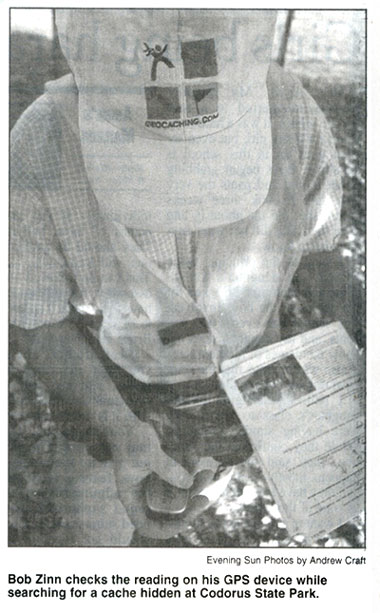

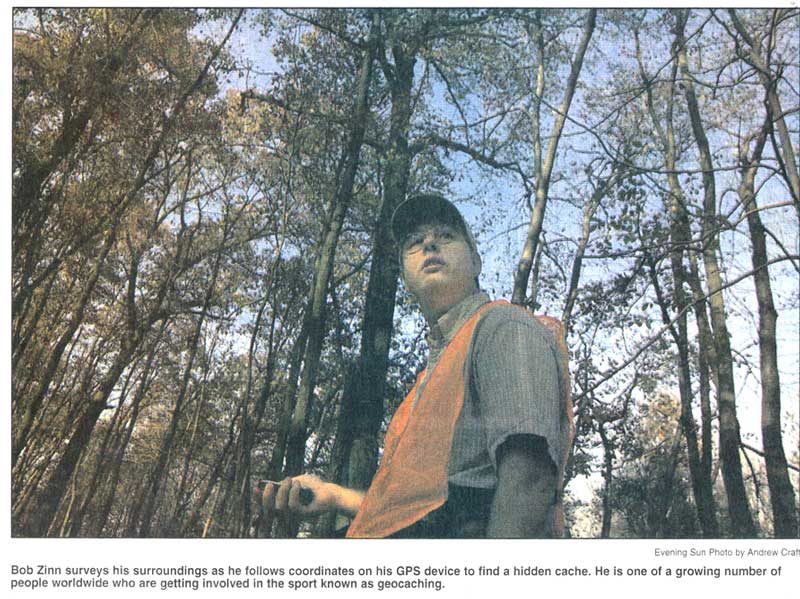

Zinn, of Adams County, is one of thousands of people worldwide hooked on the fledgling sport known as geocaching (pronounced geo-cashing).

In geocaching, one person hides a treasure for others to find, then "maps" its location using coordinates on a GPS unit. Fellow geocachers most of them self-admitted gadget fans get out their own GPS units to find the treasure, or cache.

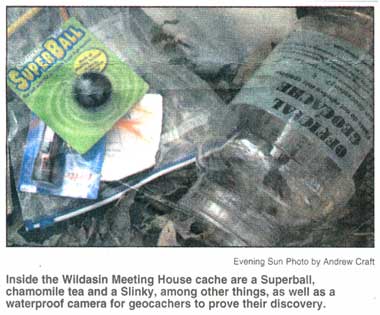

The treasures are not usually valuable. But if someone finds a cache and removes a trinket or bauble inside, he or she is expected to leave another offering in its place and to sign a logbook. Thus the game continues as other hunters find their way to the cache in a friendly competition that knows no age limit.

|

"There's more involved than just coordinates," Zinn says. Indeed, at www.geocaching.com, where players use aliases to post their latest findings and placements (and where Zinn is known as "Zinnware"), some caches include elaborate maps and clues, all intended to add to the game. "There's more involved than just coordinates," Zinn says. Indeed, at www.geocaching.com, where players use aliases to post their latest findings and placements (and where Zinn is known as "Zinnware"), some caches include elaborate maps and clues, all intended to add to the game.

Caches can be centered on a particular theme, such as history. They can involve multiple stages, such as the one Zinn and a friend (Joe Kaehler aka Highgear) placed last year at Wildasin Meeting House in Codorus State Park. That hunt takes geocachers from the grave of Revolutionary War soldier Oswald Dubs into a wooded spot slightly southwest of the cemetery.

Or they can be virtual with no physical caches, only a series of questions that take geocachers to a final destination as is required in all National Park Service sites.

"What's neat about geocaching," says Zinn, "is it takes you to places that you never would go otherwise, but they are really neat places."

Neat places like Stingray City. For that hunt, Zinn had to wade waist-deep into the Caribbean Sea to a point six miles off the Grand Cayman Islands. To prove he had reached the coordinates, he had to take a photo that showed both his GPS reading and all the stingrays gathered around him.

"I like 90 percent of the caches I go to," says Zinn, who has gone geocaching in Washington state, Arizona, even Mexico. Most of the caches he has found are closer to home.

Geocaching got its start in May 2000, when the U.S. military stopped scrambling the signal from its Global Positioning System, allowing private citizens and companies to take advantage of the precise satellite technology.

Before then, the GPS feed could be off by 100 yards or more.

Since the change in the signal, more than 72,000 caches have been hidden around the world in some 188 countries and growing.

Geocaching is similar to orienteering, a competitive sport that involves using a compass and map to find checkpoints.

But orienteering requires showing up at a scheduled event and, for those who want to compete, some degree of fitness, not to mention compass and map-reading skills.

A GPS can cost as little as $89. The technology is the same that directs missiles and tracks rental cars and oil tankers: a GPS receives radio signals from as many as 12 satellites, allowing it to determine its latitude or distance north or south of the equator and longitude the distance east or west of Greenwich, England. A GPS can cost as little as $89. The technology is the same that directs missiles and tracks rental cars and oil tankers: a GPS receives radio signals from as many as 12 satellites, allowing it to determine its latitude or distance north or south of the equator and longitude the distance east or west of Greenwich, England.

The devices also show altitude and have memories that can store maps.

For Zinn, geocaching seemed like a natural progression from his childhood fascination with maps and his adult hobbies of mountain biking and hiking.

"I like analyzing things and planning things," he added.

With a sport as new as geocaching, you might think Zinn's 193 finds would place him near the top of the pack. Not so.

That distinction belongs to "CCCooperAgency," from the greater Harrisburg area, who has found close to 4,000 caches in a little more than three years.

"Three-and-a-half caches a day, every day of the year, rain, sleet or snow," Zinn says as he shakes his head in amazement. "I think she does it for a living." He met "CCCooperAgency" once in a pre-arranged rendezvous at Thousand Steps near Huntingdon.

"She seems like a normal person," he says. The second best geocacher somebody whose alias is "BruceS" is several hundred finds behind the elusive "CC."

And, says Zinn, "the only way I could beat her is if she died now and I cached 'till I was 90."

"She's hidden more caches than I've found."

|

"There's more involved than just coordinates," Zinn says. Indeed, at

"There's more involved than just coordinates," Zinn says. Indeed, at  A GPS can cost as little as $89. The technology is the same that directs missiles and tracks rental cars and oil tankers: a GPS receives radio signals from as many as 12 satellites, allowing it to determine its latitude or distance north or south of the equator and longitude the distance east or west of Greenwich, England.

A GPS can cost as little as $89. The technology is the same that directs missiles and tracks rental cars and oil tankers: a GPS receives radio signals from as many as 12 satellites, allowing it to determine its latitude or distance north or south of the equator and longitude the distance east or west of Greenwich, England.